Known more as a symbol of global warming, the nutrient-rich plumes that trail melting giant icebergs are in fact sinking carbon deep into the ocean

Giant melting icebergs may be a symbol of climate change but new research has revealed that the plumes of nutrient-rich waters they leave in their wake lead to millions of tonnes of carbon being trapped each year.

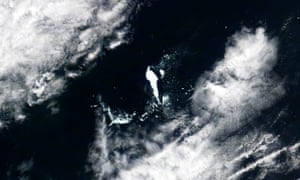

Researchers examined 175 satellite photos of giant icebergs in the Southern Ocean which surrounds Antarctica and discovered green plumes stretching up to 1,000km behind them. The greener colour of the plumes is due to blooms of phytoplankton, which thrive on the iron and other nutrients shed by the icebergs.

When these tiny algae – or the many creatures that eat them – die, they fall to the bottom of the ocean. This takes the carbon dioxide they have absorbed from the ocean surface and buries it deep below, thereby curbing the CO2 in the atmosphere and the global warming it causes.

“If giant iceberg calving increases this century as expected, this negative feedback on the carbon cycle may become more important than we previously thought,” said Professor Grant Bigg at the University of Sheffield, who led the study published in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Giant icebergs, defined as greater than 18km in length, make up half the ice floating in the Southern Ocean, with dozens present at any one time. The researchers calculated that the fertilisation effect of the icebergs in the normally iron-poor waters contributes up to 20% of all the carbon buried in the Southern Ocean, which itself contributes about 10% of the global total.

“We detected substantially enhanced chlorophyll levels, typically over a radius of at least four to 10 times the iceberg’s length,” said Bigg. The chlorophyll levels remained 10 times higher than in the surrounding ocean for at least a month and up to 200km behind the iceberg. Some increase in phytoplankton was seen as much as 1,000km behind the iceberg in a few cases.

The discovery was a surprise as previous studies of small icebergs, or using ship-based measurements, has suggested a much smaller fertilisation effect. The largest iceberg analysed in the new study was more than 50km long.

Advertisement

The impact of global warming on melting ice in Antarctica, much of which is far below 0C, has been widely studied. Biggs and his colleagues note that satellite gravity data show a 5% increase in ice discharge from the continent over the past two decades.

In 2014, two separate teams of scientists found that the collapse of the Western Antarctic ice sheet is already under way and is unstoppable. The loss of this entire ice sheet would cause up to 4m of sea-level rise in coming centuries. In 2015, researchers found the melting of floating ice shelves around Antarctica was faster than thought, potentially unlocking extra sea level rise from larger ice sheets jammed behind them.

Professor Andrew Shepherd, director of the Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling at the University of Leeds, said in 2015 that the rates of ice shelf loss were unsustainable and could cause a major collapse. This is already occurring at the massive Pine Island glacier, where ice loss has doubled in speed over the last 20 years as its blocking ice shelf has melted.