As February breaks another global record for the hottest month, we assess the impact of El Niño on the recent succession of extraordinary weather events

Yet another global heat record has been beaten. It appears January 2016 – the most abnormally hot month in history, according to Nasa – will be comprehensively trounced once official figures come in for February.

Initial satellite measurements, compiled by Eric Holthaus at Slate, put February’s anomaly from the pre-industrial average between 1.15C and 1.4C. The UN Paris climate agreement struck in December seeks to limit warming to 1.5C if possible.

“Even the lower part of that range is extraordinary,” said Will Steffen, an emeritus professor of climate science at Australian National University and a councillor at Australia’s Climate Council.

It appears that on Wednesday, the northern hemisphere even slipped above the milestone 2C average for the first time in recorded history. This is the arbitrary limit above which scientists believe global temperature rise will be “dangerous”.

The Arctic in particular experienced terrific warmth throughout the winter. Temperatures at the north pole approached 0C in late December – 30C to 35C above average.

Mark Serreze, the director of the US National Snow and Ice Data Centre, described the conditions as “absurd”.

“The heat has been unrelenting over the entire season,” he said. “I’ve been studying Arctic climate for 35 years and have never seen anything like this before”.

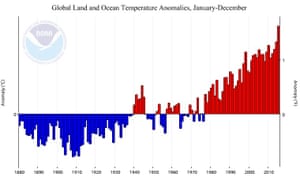

All this weirdness follows the record-smashing year of 2015, which was 0.9C above the 20th century average. This beat the previous record warmth of 2014 by 0.16C.

Facebook Twitter Pinterest

Facebook Twitter Pinterest These tumbling temperature records are often accompanied in media reports by the caveat that we are experiencing a particularly strong El Niño – perhaps the largest in history. But should El Niño and climate change be given equal billing?

No, according to Professor Michael Mann, the director of Penn State Earth System Science Centre. He said it was possible to look back over the temperature records and assess the impact of an El Niño on global temperatures.

“A number of folks have done this,” he said, “and come to the conclusion it was responsible for less than 0.1C of the anomalous warmth. In other words, we would have set an all-time global temperature record [in 2015] even without any help from El Niño.”

Global surface temperature is the major yardstick used to track how we are changing the climate. It is the average the UN Paris agreement refers to.

But the atmosphere doesn’t stop at the surface. In fact 93% of the extra energy trapped by the greenhouse gases humans have emitted gets sunk into the oceans – just 1% ends up in the atmosphere where temperature is most often and most thoroughly measured. During El Niño, which occurs every three to six years, currents in the Pacific Ocean bring warm water to the surface and heat up the air.

Jeff Knight from the Met Office’s Hadley Centre, said their modelling set the additional heat from a big El Niño, like the current one, at about 0.2C. He said wind patterns in the northern hemisphere had added another 0.1C to recent monthly readings.

Advertisement

“The bottom line is that the contributions of the current El Niño and wind patterns to the very warm conditions globally over the last couple of months are relatively small compared to the anthropogenically driven increase in global temperature since pre-industrial times,” he added.

Steffen said the definitive assessment of this El Niño and its effect on the world’s temperature would only be possible once the event had run its course (it has now peaked and is expected to end in the second quarter of this year). But he agreed that past El Niño cycles could be an appropriate guide for the order of magnitude of the effect.

The picture becomes less clear cut when we talk about monthly records. Even weather trends can have small effects on the monthly average temperature, said Knight. The effect of El Niño traditionally increases as it dies, so Mann believes it may have added more than the “nominal” o.1C during the past three months.

In the Arctic, the effect of El Niño is poorly understood but likely to be weak, said Knight. “Given that the Arctic has been very warm for a number of years, with record low sea ice, it is more likely that the warmth there currently is part of a long-term trend rather than the response to a episodic event like El Niño.”

Steffen says quantifying the relative contributions of El Niño and climate change on a monthly or even annual basis cannot help to answer how fast the world is warming. Only trends over 30 years really matter.

But the pile up of records we have had in the early part of this century are significant. All things being constant, record hot years should occur once every 150 years. Yet 1998, 2005, 2010, 2014 and 2015 have all been record breakers.

Advertisement

A study published in January found that even without last year’s mammoth anomaly such a run was 600 to 130,000 times more likely to have occurred with human interference than without.

“The fact that you are getting records so close, one after the other is really striking. And that is symptomatic of that long-term trend,” said Steffen.

But while they may be poor signals for long-term climate change, record hot months and years do have an immediate and tangible impact.

“It’s making heat waves worse. Here in Australia it bumps up the bushfire danger weather really fast. It tends to lead to drier conditions in our part of the world. These things are exacerbated by El Niños, so I don’t want to downplay the importance of them for human suffering,” said Steffen.