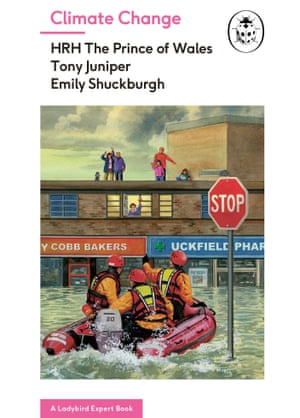

Ladybird books will this week publish a new title on climate change. Co-authored by the Prince of Wales, the polar scientist Emily Shuckburgh and myself, the book is intended as a plain English guide to the subject for an adult readership. Short, peer-reviewed text sits alongside beautiful new paintings by Ruth Palmer to illustrate the basic briefing.

It has already been greeted in some quarters as another controversial intervention by our future king. But while it’s easy to fall behind that line of thinking, it is an increasingly mistaken one. For despite the impression created in some quarters, the truth is that climate change is not controversial. The basic facts are established and increasingly embedded in policy.

We know, for instance, that the global average temperature has during recent decades gone up. This is largely because of the accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, the concentration of which is rising because of human activity. In turn, the altered composition of the atmosphere is leading to changes that range from more extreme weather to reduced ice and snow cover and from unusual seasonal patterns to rising sea levels. All that is now established fact derived from careful observation and analysis.

These broad findings are increasingly reflected in policy choices and the business strategies of major companies. While there are those in elected office in some countries who take a non-scientific view, and some vested commercial interests that resist low carbon policies, there is less political division than is sometimes suggested.

For example in 2015, nearly every country on Earth (most of them some sort of democracy) signed up to the Paris climate change agreement. That legally binding treaty was not entered into lightly and revealed a level of political consensus visible on very few other issues.

Facebook Twitter Pinterest

Facebook Twitter Pinterest In the UK, and despite several major media organisations continuing to pour doubt and confusion into the public discourse, we have a strong political foundation for action, as laid out in the form of the 2008 Climate Change Act, for example.

I launched the campaign for that act when I was the director at Friends of the Earth and one reason why it was possible to gain cross-party political backing for such a law was the work of Britain’s world-leading scientific institutions, including the Met Office and the British Antarctic Survey. Through supplying policy-makers with the findings of their research, they helped to shape understanding to the point where official foundations for action were laid.

With the science clear and the politics (in this country) quite robust, it is predictable that those with perspectives on climate change founded more on ideology than data will go for the messenger rather than the message. The Prince of Wales should keep “his mouth shut” was, for example, the recommendation of the Daily Mail in the wake of an article penned by the heir to the throne to mark the publication of his new book.

While the Mail and some other papers evidently won’t agree with his views on this subject, they might wish to reflect for a moment on the role of our monarchy. In the absence of a written constitution, perhaps the closest we’ve got to an accepted view on what it is for and where its right lie comes from the Victorian essayist and long-serving editor of the Economist, Walter Bagehot.

He wrote in 1867 in the English constitution that the monarchy has “the right to be consulted, the right to encourage, the right to warn”. I can think of few issues where exercising those rights fits the bill more closely than in relation to the ever less controversial matter of climate change.