This is the first time experts know of a slide of construction waste, but it fits a pattern of catastrophes that have become endemic to developing countries

The deadly landslide that buried part of the southern Chinese city of Shenzhen beneath a tide of red mud on Monday may be a devastating new consequence of China’s urban explosion, an expert has warned.

The destruction of 94 acres of the Guangming New District, which had sprung from the rice paddies in just a few decades, was sudden but a long time in coming. Even as the the neighbourhoods and factories were being built, the mountain of refuse that would destroy it all was piling up.

Professor Dave Petley, pro-vice chancellor for research and enterprise at the University of East Anglia , said Shenzhen was the first time he had heard of a slide of construction waste. Almost always this type of accident can be traced back to the slag heaps of the mining industry. The government would now be scrambling to establish whether this was a one-off incident, or the first of more to come.

“To me, this is completely new,” he said. “Huge amounts of construction debris is being generated in China. This is being stored somewhere. Are there other dumps like this one? I don’t know the answer to that, but I think the Chinese authorities will need to know that pretty quickly.”

But while Shenzhen could set a dangerous new precedent, it fits a familiar pattern of landslide catastrophes that have become almost endemic to a group of developing countries where progress often trumps safety.

“These sort of waste-flow slides are depressingly frequent and entirely preventable. We repeatedly see big piles of man-made waste sliding and engulfing populations. Far more people are killed than people generally realise,” said Petley.

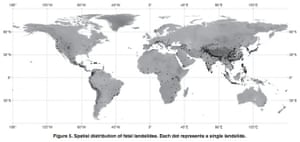

In the first major global survey of its kind, Petley recorded 2,620 fatal landslides and 32,322 deaths from 2004-2010. That’s 4,617 people buried alive every year. Just three weeks ago, more than 100 jade miners in Burma were buried as they slept in their quarters by a wall of sludge.

“More than 70% of landslides that kill people have an element of human cause,” he said. Although he added that it was difficult to say whether or not more fatal accidents were occurring today because the historical data is very poor.

Advertisement

“Landslides happen all the time,” Dr Farrokh Nadim, technical director at the Norwegian Geotechnical Institute, told the Guardian. “Most of them are part of the natural geological process.”

But almost all landslides occur after sudden, unusually intense rainfall. Climate change has begun to bring more extreme rainfall events to some parts of the globe. But so far the events are too complex and data too patchy to define any trend. Nadim said this work was being done, but in the meantime, there is no reason to think climate change would not compound the landslide problem in some parts of the globe.

Overall landslide frequency is roughly the same across the mountain ranges of the world. But deadly landslides overwhelmingly occur in poor countries. Roughly one-third of the deaths occurred in South America, but the real global hotspot is Asia.

Particularly badly affected are China, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. This is in part because of the density of the population and the topography – steep, crowded Himalayan slopes are of course more prone than level plains.

The Asian region is experiencing the most rapid proliferation of urban humanity in history. The great sprawl of China’s cities has welcomed 500 million new people in the past three decades. Infrastructure is being thrown up with unmatched ferocity and deadly landslides are a direct result. In many Asian countries, said Nadim, “the biggest threat of landslide is human activity”.

Facebook Twitter Pinterest

Facebook Twitter Pinterest “There is a tendency that if the area is being newly developed and there is construction, which has such a high tempo that it is almost impossible to control, that you get these human-triggered slides,” he said.

Accidents do not necessarily occur because of a lack of engineering expertise, said Nadim. “In China, they have more landslide experts than all the EU countries combined.” But in the mad rush for progress, corners get cut and too many people look the other way. Reports from Shenzhen indicate the government had been aware of the problem for years and banned builders from dumping waste on the mountain that gave way on Monday. But they were ignored. According to reports, trucks were still piling it up last week.

“There is a really high correlation between the corruption index and natural disasters,” he said. “People just want to make high profit with cheap solutions that cost them nothing.”