Where only a few weeks ago there were swathes of vivid purples, blues and pretty much any other colour you fancy, now there is just grey and white.

Corals in the northern section of Australia’s vast Great Barrier Reef – a length of more than 1000km or so – have become the latest and most famous victims of the third global “mass bleaching” of corals since 1998.

“It’s pretty confronting,” says Prof Terry Hughes, a leading coral scientist who has been spending recent days in a helicopter surveying the reef.

Of the 520 reefs he flew over, only four have managed to retain their colour. He’s back in the skies to look further south in the coming days.

“The Great Barrier Reef is today a diminished place from what it was a month ago,” Hughes, of James Cook University, told me.

“We can’t climate proof this reef. We have seen the most pristine part of the reef take a direct hit.”

As Hughes travelled further north to parts of the reef outside the boundaries of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, he saw corals “blitzed” in the Torres Strait.

Corals get their striking colours thanks to the zooxanthellae algae that they live with.

But when the corals and the algae are stressed, they separate, leaving a bare white skeleton behind.

In mass bleaching events, the stress comes when corals bathe for too long in unusually warm ocean waters.

This is the point at which the Great Barrier Reef and the world’s fossil fuel industry come into direct conflict.

So far, the reef is losing.

Record ocean temperatures

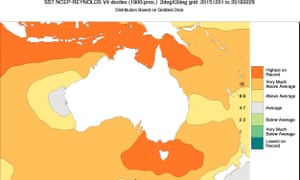

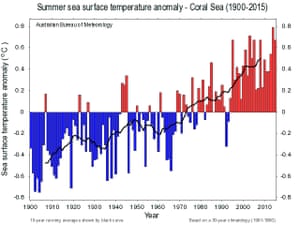

According to the Bureau of Meteorology, the sea surface temperatures (SST) in the Coral Sea region have been the highest on record for this most recent summer wet season.

The BoM’s ocean temperature record goes back to the year 1900. As this chart shows, SSTs overlapping the northern parts of the reef have been the highest of any summer (December to February) on record.

Facebook Twitter Pinterest

Hughes said that in 1998, 2002 and this current GBR bleaching event, the areas of the reef that bleached matched “perfectly” the areas with unusually high SST.

The record warm oceans that have been stressing the corals in recent weeks are part of a long-term trend of warming ocean temperatures around the globe, including the waters off Australia.

Facebook Twitter Pinterest

The cause of that warming trend is the extra heat being retained by the Earth’s climate system thanks to the burning of fossil fuels like coal, oil and gas that add greenhouse gases to the atmosphere and the oceans.

Not surprisingly, the coal industry has tried to muddy the scientific waters on this key point.

As I’ve written here before, the fact that Australia’s expansion of its coal export industry takes ships on a route straight through the reef could be seen as something of a sick joke.

When I asked Hughes about the cause of the bleaching, he replied simply: “Global warming – the link is incontrovertible.”

What’s also important to understand is that the corals in the north that have been bleached, are probably the least impacted by human activity across the GBR.

Current and previous governments at state and federal levels, of both stripes, have increased investments to cut the amount of nutrient-rich waters and pollution running into the reef from farms and development along the coast.

But scientists, including the government’s own, have been warning for years now that the most important threat to the reef is from climate change.

Hughes says that while it is true that some coral species are more resilient to bleaching than others, this gives him little comfort when he had witnessed even the most resilient species bleached in recent days.

“If half the corals bleach you will sea a pattern of winners and losers. But if all the corals are bleaching, then there are no winners. And they are all bleaching,” he says.

Hughes says it’s also misleading to pin the blame for the current bleaching event on the El Niño climate pattern.

Evidence from long term coral records did not show the signatures of coral bleaching, even though those corals would have been through many El Niño events. Hughes explains:

It’s only since 1998 that the extra spikes [from El Niño] cause problems. We had El Niños for centuries but they don’t show bleaching.

Because it’s pristine [in the reef’s north], it’s not got the issues with run-off [from agriculture and coastal development] and it should better be able to bounce back.

But if it takes 10 years, what’s the chance of getting another El Nino before 2026? It’s high. We will be in trouble if the return time is less than the recovery time.

In another bitter slice of irony, Hughes says that the central and southern sections of the reef probably “dodged a bullet” but this was only thanks to the cooling influence of the tail-end of the same weather system that caused the devastating cyclone in Fiji.

Coral lobbying

Advertisement

When in November 2014 the US president, Barack Obama, told a crowd at the University of Queensland that the “incredible natural glory of the GBR is threatened”, Australia’s foreign minister, Julie Bishop, ignored the advice of her government scientists to lead a chorus of correction.

“Of course the Great Barrier Reef will be conserved for generations to come and we do not believe that it is in danger,” she said.

In 2015, the Australian government spent $100,000 flying officials around the world to convince members of the World Heritage Committee not to place the reef on the “in danger” list.

The lobbying effort was a “success” but the victory must surely now be ringing hollow.

Hughes and other coral scientists are angry that years of warnings about the reef’s future have gone unheeded.

Hughes said there was a “disconnect” between the science and Australia’s policies of developing coalmines.

Another world-leading coral scientist is Prof John Pandolfi, of the University of Queensland, who told me he had “several reactions all at once” to the bleaching playing out on the reef.